While the Supreme Court is currently deciding the constitutionality of race-based affirmative action in Fisher v. University of Texas, it’s worth taking a look at the effectiveness of the practice.

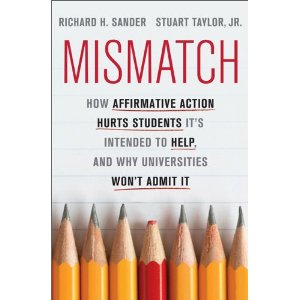

In a new book Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It, Richard Sander, a law professor and economist at UCLA and Stuart Taylor Jr., a Washington-based journalist, argue that the affirmative action policies of the past four decades have hurt Black and Latino students more than anyone else.

The argument is simple – by lowering the standards of admission, we are sending millions of Black and Latino students to universities that they are not prepared to be in. Instead of going to “less competitive but still quite good schools”, these minority students are admitted to elite universities where they are at a competitive disadvantage as compared with their White and Asian peers. In an excerpt published in The Atlantic, Sander and Taylor show mounting evidence from the past decade:

- Black college freshmen are more likely to aspire to science or engineering careers than are white freshmen, but mismatch causes blacks to abandon these fields at twice the rate of whites.

- Blacks who start college interested in pursuing a doctorate and an academic career are twice as likely to be derailed from this path if they attend a school where they are mismatched.

- About half of black college students rank in the bottom 20 percent of their classes (and the bottom 10 percent in law school).

- Black law school graduates are four times as likely to fail bar exams as are whites; mismatch explains half of this gap.

- Interracial friendships are more likely to form among students with relatively similar levels of academic preparation; thus, blacks and Hispanics are more socially integrated on campuses where they are less academically mismatched.

The most damning piece of evidence though is from California where, in 1998 Continue reading “Affirmative Action Hurts Minorities the Most”

We are filling colleges with too many unprepared students who don’t want to be there in pursuit of a misguided idea of prestige.

We are filling colleges with too many unprepared students who don’t want to be there in pursuit of a misguided idea of prestige. College degrees may no longer get you a job, but tuition costs continue to rise and student debt continues to accumulate.

College degrees may no longer get you a job, but tuition costs continue to rise and student debt continues to accumulate.